The Farmers ~ Part Two

The Farmers ~ Part Two

The Farmer From Killenard

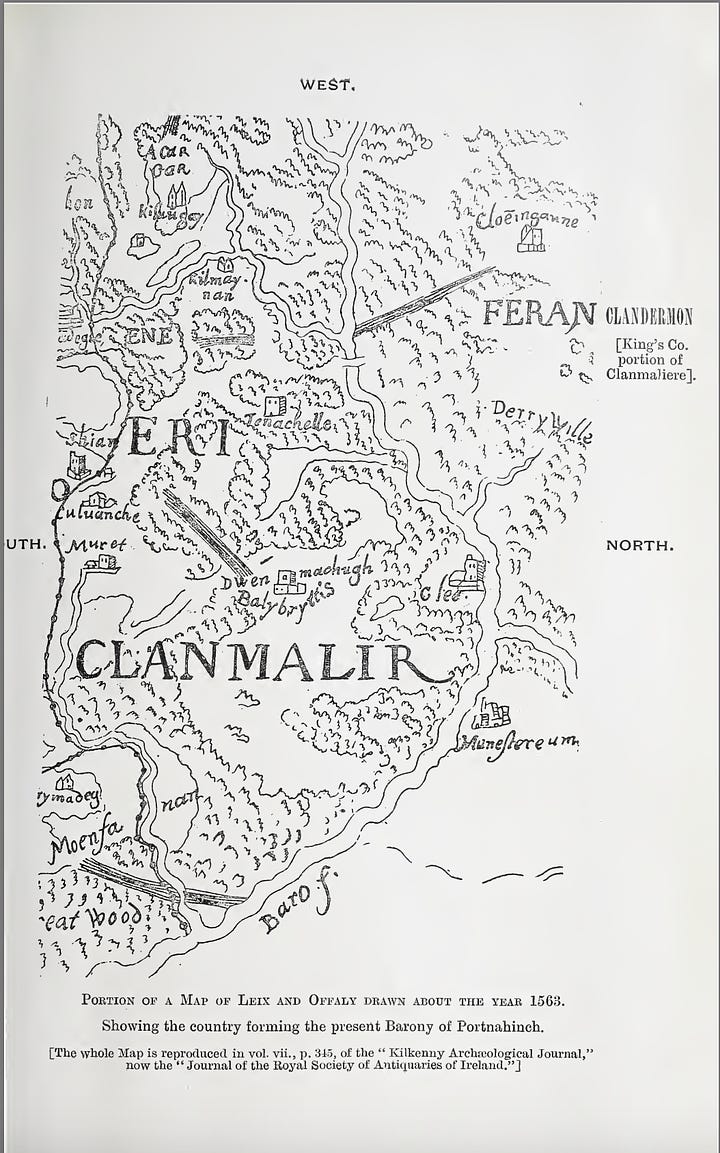

The Kelly family came to America from Killenard, in the Parish of Lea, which was a part of the Barony of Portnahinch, in the Queen’s County1.

The barony sat in the northeastern part of the county, where the River Barrow defines portions of its borders with the King’s County and with County Kildare. To the east, on the Kildare side of the Barrow, lies the town of Monasterevin, in a barony of the same name; and south of it are the townlands that comprised the Barony of West Offaly.

Coill an Aird. In Irish, it means ‘Wood of the Height’; it is the local name for a group of townlands just south of the town of Portarlington. Ballycarroll, Ballybrittas, Tierhogar, and Rathmiles are said to lie along the Sli Daile, one of the five ancient roads of Irish lore. Bordering Ballycarroll to the east are the townlands Ballentogher and Killinure, which sit on the border with Kildare.

The ‘Height’ refers to a low hill, upon which a windmill had long stood; grain had been milled there by local farmers for centuries before it fell into disrepair, sometime in the early 1800s.

The townlands2 were really no more than clusters of farms, varying in their sizes and populations. Families had farmed the land for generations. Through that time, the townlands became defined, and had acquired their names. The old Irish names are lyrical. They tickle the imagination with imagery of a verdant checkerboard, made of lush pasture and stone walls; thatched roofs sat atop neatly kept cottages, surrounded by tidy gardens. Often, history reveals a less colorful picture, lying just underneath the patchwork blanket of green.

As with most of the Irish Catholic majority across rural Ireland, the Kelly family inhabited their ancestral land as tenant farmers. These were generally of smaller acreage, and worked by members of the family. Farms ranged from a single to perhaps ten to twenty acres; half of the farms in Killenard were under five acres. The farmer paid an annual rent to the landlord; generally with coin, and with sometimes labor, or a portion of the harvest. In addition, English law required they pay a church tax ~ a tithe ~ in support of the Protestant parish church. This often meant little for the support their own local Catholic priest, or towards any meaningful improvement to their own condition.

For the future leaders in the American colonies who were, at the time, planning their own brazen act of rebellion, Ireland would have stood as a stark warning to those who would defy England’s might.

Michael Kelly was born in 1773; and the heroes of Ireland were long dead.

In 1649, Oliver Cromwell had led his army on rampages across the Irish countryside; a four year campaign of death and destruction, to end the ‘Eleven Year War’. Irish self rule had come to an end.

For the people of Killenard and the barony, the voices of those times would surely have echoed around them in the ruins found amid their townlands. Ballybrittas had been the stronghold of the O’Dempsey Clan (or Sept) and the kingdom of Clanmalire, long before the counties had been claimed by edict and renamed for English royals. For some three hundred years, Clanmalire had kept “The Pale” ~ that area of England’s influence ~ from further spreading into the heart of Ireland.

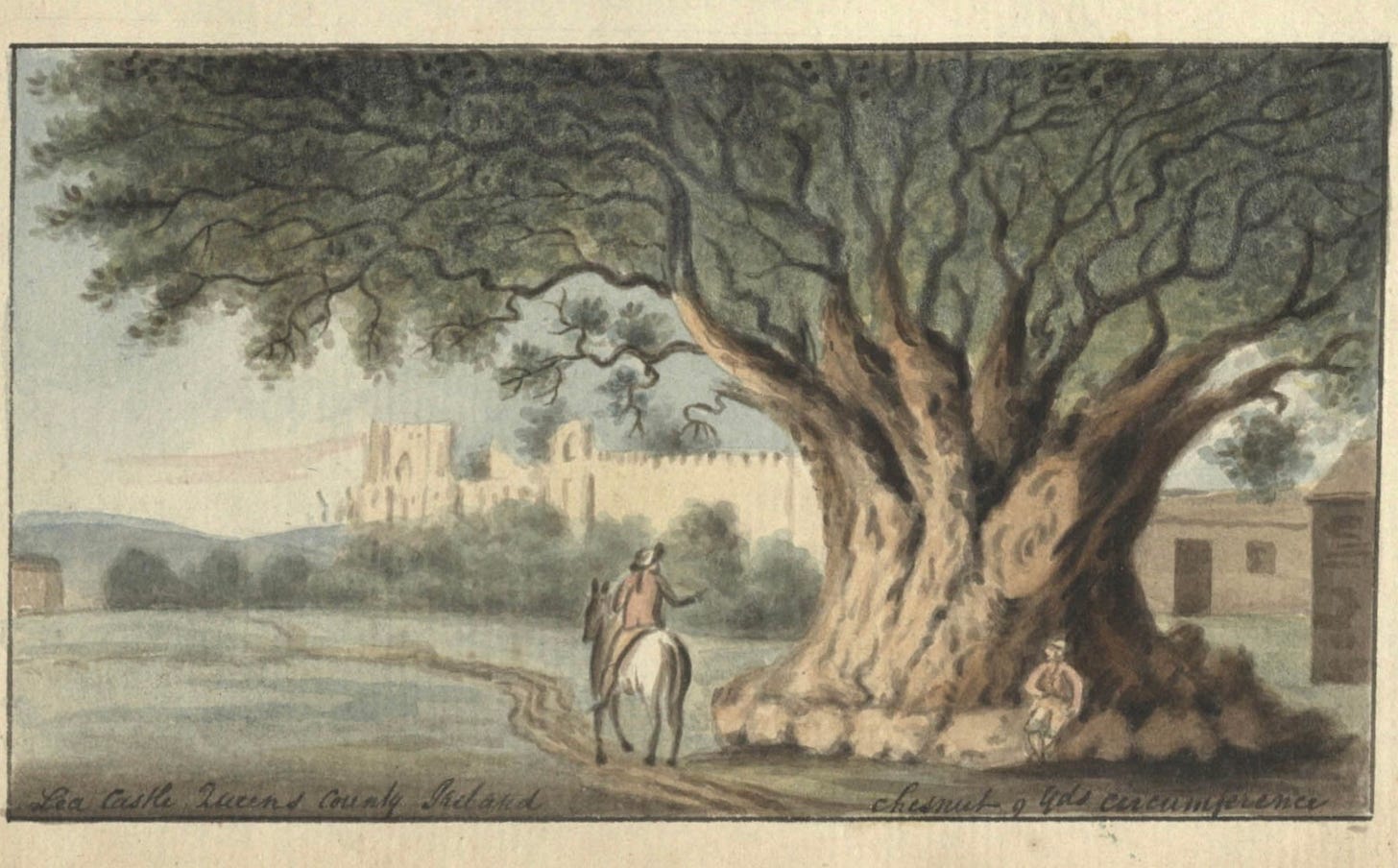

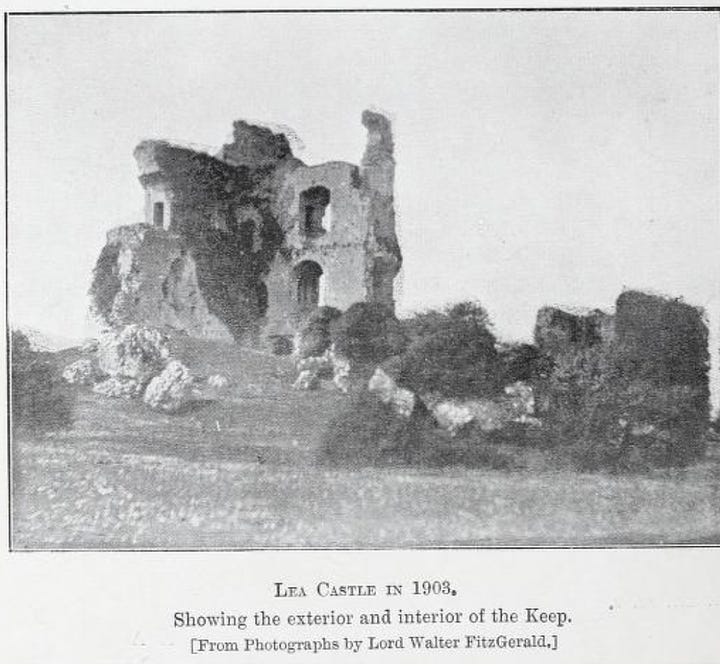

The old cemetery in Tierhogar, barely a stone wall left to mark the place where a medieval church had once stood. Lea Castle, the last of its four towers standing like a weary sentry on the banks of the Barrow. Already ancient, it had been taken, re-taken, burned and rebuilt; it was broken and dismantled by Cornwall’s men, in 1650.

The last of the powerful O’Dempseys had been killed or banished, their territories seized; their castle towers toppled and strongholds destroyed. Many thousands of Irish were sent to the island colonies as slaves for the plantations; others to the Virginia colony. The remaining Catholic land owners were resettled to the less populated western counties of Ireland. The peasant farmers who had remained found themselves occupiers; leasing their farms on the estates and plantations owned by the English and Anglo-Irish gentry. Later called the “Protestant Ascendancy”; by the beginning of the 18th century, the number of Catholic land owners had systematically been reduced from 60% in 1600 to a meager 8-10%.

Every generation of Kelly, it seems, had seen upheaval during his lifetime.

The ‘Wood’ at Killenard was a clearing in the trees, just below the old windmill. It was where the local Catholics had gathered in secret for their outdoor services, after as series of English penal laws had outlawed their priests and churches.

Doire Uachtair~ The Upper Oaks; Doire Laith ~ The Green Oaks; Bóthar an Doire ~ The Road of the Oaks. The old language was heard less, by this time; and old places had taken new names, when spoken with an English tongue. Derryoughter, Derrylea, Barraderra; the townlands along the Barrow name a plundered treasure. The great old forests had been cut and carted away centuries ago, leaving scruffy pasture.

The old places and the stories of their Clans and Kings, and their loss; told amid their broken churches and forts; these things ~ like their Catholic faith ~ were, by Michael Kelly’s time, as much a part of the identity of his people as the ruins were part of the land.

Still, their lives were filled with more immediate concerns than the old timers’ stories. Even if better circumstanced than many, the farmers of Killenard were sustenance farmers, and agrarian issues were ever present; a life of toil was a daily reality. And they were still subject to the same Penal Laws as all of Ireland’s Catholic majority. Increasingly, a farm had become nearly impossible to obtain; and they were becoming smaller, due to inheritance and lease laws.

Portarlington and Monasterevin had become prosperous market towns by the mid-eighteenth century, and the Killenard townlands lay between them. When Michael and his siblings were still children, a branch of Ireland’s Grand Canal had been completed; it cut across the Barrow from Monasterevin and into Killenard. The “Barrow Line” made its way through the townland of Ballentogher and south, running parallel to the Barrow on its way to the town of Athy. The Grand Canal connected Dublin’s River Liffey with the River Shannon, in the west.

In Monasterevin, a local Gentleman ~ a landlord named Cassidy ~ had opened a distillery which provided local employment, and a need for the grain harvests. The new canal had brought an increase to commerce. There were a number of schools in Portarlington, which boarded the children of Dublin’s elite. Portarlington had been an early ‘plantation town’; in was established in 1664, after the restoration of Charles II, to his former Home Secretary, Sir Henry Bennett. Bennett brought a group of fifteen French Huguenot families to Portarlington in 1694; Protestant refugees who’d been driven out of France. The town would soon have two churches ~ the Church of Ireland for the Anglicans, and the French Church, for the Huguenot Protestants. The architecture of the town developed a unique quality; that of a French village.

It’s no doubt due to this proximity that the Catholic community in this part of Queen’s County were, in at least some ways, in a better state than much of the country. The old prejudices were ever present; but by most accounts, the Protestant land owners in this part of the county were the decent type. This was reflected in accounts of the better condition of the farms in most of Portnahinch.

Even the best farm house bore no resemblance to the wood framed, clad, and shingled structures of Colonial America in that same era. That is, of course, notwithstanding the Georgian-style Manor houses of the Protestant landlords. The cottages ~ or cabins ~ were of the same basic design. They were single-storied and single-room deep; the thick walls were built of clay and whitewashed with lime, to hold back the damp. Dirt floors, tamped down from use and age; in the main room was the open hearth, above which a low roof built of hewn timbers, branches, and oat thatch kept away the weather. A bedroom or two, one on either side. Modest furnishings and bedding; perhaps a cupboard, to hold their cookware. Any outbuildings for animals would be of the same materials. However, the quality of the homes varied, depending upon one’s condition. The poorest of the farms had but a squat, dark, windowless cabin made of damp turf brick. The family might occupy the cabin with their few precious farm animals; peat smoke would have billowed from a crude door.

During Michael’s young life, the host of grievances had again been building the frustrations around Ireland. An alliance between the Anglo-Irish gentry, who sought more control over their own affairs, and the Catholic Confederation, which, for months, had rallied young farmers’ sons across Ireland ~ embittered and angry at their condition, and charged by stories of the American and French Revolutions ~ and formed them into groups of rebel fighters.

But the 1798 Rebellion in Ireland would not see similar outcomes.

On the 24th of May, planned rebellions took place in the towns around County Kildare, and across Ireland. However, a number of planned strategies failed to execute; leading to cascade of failures that would doom the rebellion. The next night, a group of rebels staged an attack on Monasterevin. Some 1300 men, most of them from townlands south of the town, formed three columns of attack: one, along the canal, another from the turnpike, and the third on the main street. Fiery skirmishes took place in the streets between the rebels and the 80 yeoman cavalry charged with protecting the town. The rebels eventually fled the fight; leaving 63 of their young men dead, and a number of the infantry dead or wounded.

The fighting would continue for many months in various parts of the country; but the insurrectionists had been cursed from the initial series of missteps. After the attack at Monasterevin, some of the fighters continued into the Queen’s County, causing havoc; others went on to join a camp of rebels gathering on the Curragh, a plain south of Kildare town. The luckier ones returned home to their farms. For the townlands along the Barrow, the Rebellion seemed to have ended nearly at its start; but it hadn’t, yet.

Just four days later, on the Curragh, at a place called Gibbet Rath, one to two thousand rebel fighters had gathered for the second of negotiated surrender-for-amnesty agreements, struck with the generals of the local militia. On May 29th, a Major-General Duff, of Limerick, arrived with his own troops and surrounded the men, who had just surrendered their weapons; he then began a long tirade, forcing many of them to kneel in submission. As is common, the fog of war conceals the spark that caused what happened next; Duff’s militia men began firing into the mass of unarmed men. In an instant, several hundred sons of Irish farmers had been slaughtered. The Massacre at Gibbet Rath would be added to a centuries long list of atrocities.

In June, at the market house in Portarlington, rebels had been rounded up to witness the barbaric executions of their suspected leaders. Some of them would be deported to the colonies. Others were imprisoned; most of them briefly, only to be sent home. Rebel or otherwise, laborers were still needed for the fields.

As the world entered a new century, Ireland was left reeling from another crushing, death-dealing defeat; no different than those suffered in the prior century. Killenard, and all the townlands on the Barrow and beyond; not one person would’ve been left untouched by the savage and sudden loss of so many of their young men. It surely would have changed many things in the baronies; a diminishing of goodwill, the strengthening of prejudice; and hopelessness, for any relief the their condition.

Every generation of Kelly had seen upheaval during his lifetime; and Michael Kelly’s generation had been no exception.

In 1810, at the age of 37, Kelly married Mary Ann Cadoga3; she'd also been born in Killenard, in 1782. By custom, Michael could not have married until he’d acquired his own farm. Given the dates involved, it’s likely that Mary Ann had inherited a portion of her father’s farm, upon his death in 1800. Lucky for Michael Kelly; as she would have certainly have had her pick of the bachelors, if this were indeed the case!

The Kellys would have at least seven children; six would leave Killenard with their parents. Catherine and Thomas, who were both ‘of age’; Julia, Delia, Joseph, and Michael, the youngest, born in 1824.

Michael, Mary Ann, and their children left behind the farms of their parents and their parents’ parents; all who’d come before them. They’d left behind family and kin. All of the upheavals, heaped upon the indignities, which those past generations ~ and their own ~ had endured; a single one or any combination of these things would have been reason to leave. Still, they had one very powerful reason to stay. In the face of all of it, Killenard was the place where the Kellys had thrived; when they were able. Coill an Aird was home. But the Kelly family did leave behind the familiarity of those old places. For something must have offered a promise great enough to break that attachment; let alone to face the risk ~ the apprehension.

Michael was nearly sixty years old, when he and his family left Killenard for America. No matter the reason for leaving the place, Kelly’s pursuit seems clear, and an interesting counterpoint to that of young Moses Beach ~ his future, not-yet-famous son-in-law. Beach had left behind the family farm and towns of New England for his own ‘new world’. Bolstered by his heroes, Moses sought to make a name for himself in the new era of industry. But Michael’s heroes were long dead; and he’d seen them killed again. Michael Kelly was coming to the new world for the life which Beach had left behind; he just wanted to be a farmer on his own land.

In 1834, Michael Kelly purchased the first 80 acres of the Kelly Farm in Rocky Hill, from a farmer named Gershom Bulkley.

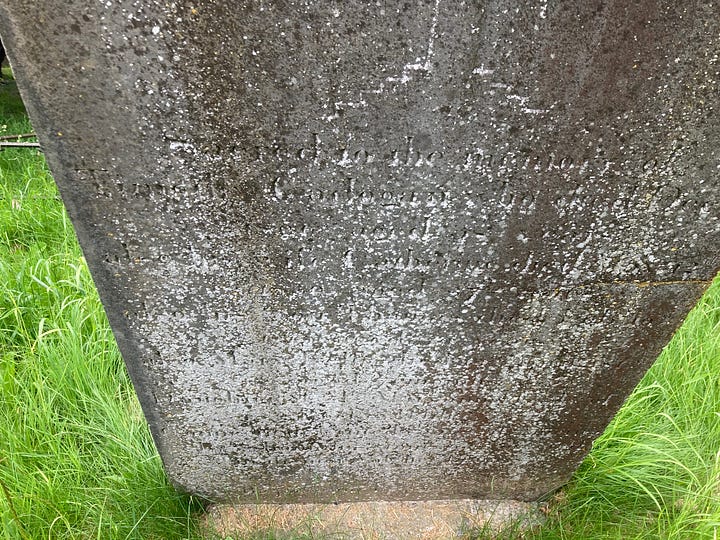

From their new world, the Kellys would remember their home of Killenard; placing a marker there, for those left behind. Sometime after the death of her mother in 1839, Mary Ann arranged for a memorial stone to be placed in the old graveyard in Killenard. It was as the parish church ~ St. John’s Church ~ was building a new school there. The stone is weathered and mossy; all but unreadable, today:

Sacred to the memory of Timothy Cadogan who died Dec 3rd (1800) aged 58 years.

Also his wife Catherine died May 12th 1839 aged 87 years.

Also his son Thomas died Feby 10th 1813 aged 19 years.

Also Mary Kelly died 11th April 1812 aged 7 Months.

Daughter of Mrs. Mary Anne Kelly Rockey Hill, Connecticut, United States of America,

by who this Stone was erected in Memory of her family.

Requiescent in peace.Next: Mr. Beach of Barclay Heights

It was renamed County Laois (pronounced as “leesh”) ~ along with neighboring Kings County, renamed County Offaly ~ after the formation of the Republic of Ireland, in 1922.

In Irish, ‘an baile fearainn’ (baile = home/town fearann= land/territory) aka town-land pre-dates the Norman invasion; the smallest territorial unit to have survived since medieval times.

While she spelled her name as “Cadogan”, it’s more likely that Mary Ann’s surname was a misheard/misspelling of “Carrigan”. The latter name is prevalent in the parish; the former name is principally found far south, in Co Cork

Comments

Post a Comment